Rating: 3/5

“Give this man satin undies, a dress, a sweater and a skirt, or even the lounging outfit he has on, and he’s the happiest individual in the world. He can work better, think better, he can play better, and he can be more of a credit to his community and his government because he is happy.”

It’s difficult to know where to begin. Glen or Glenda, Ed Wood’s feature debut and his most overtly personal movie, is easily one of the most (in)famous badfilms around – so much so that it has become something much more. Watching it without any knowledge of the filmmaker is an entirely different experience, but I can barely remember those days. Now my head is filled with Ed Wood trivia, anecdotes, interviews with his friends and colleagues, and all of these have inevitably, irrevocably altered my perception of the film. Let me clarify my position. Glen or Glenda is a bad movie. It’s inept and incoherent, obviously low-budget, and clearly spliced together from a mass of unrelated stock footage. Yet it’s also deeply personal, oddly progressive (with regards to certain groups of people; in contrast, the gay community are entirely vilified), and strangely fascinating. Ed Wood is not a good director in classical terms, but there is something about Glen or Glenda. In many ways, Wood is barely responsible for this re-evaluation – it’s the amount of extratextual information available that transforms way the movie is now viewed.

Viewers who are unaware of the conditions under which Glen or Glenda emerged will be understandably bemused by it. In the context of classical narrative cinema, it is truly inept – following the death of a transvestite, a police inspector (Lyle Talbot) visits a psychiatrist (Timothy Farrell) for advice. The good doctor relates two stories: the first follows Glen, a transvestite engaged to Barbara but afraid to admit his fetish to her; the second follows Alan, a pseudohermaphrodite who finally becomes Ann thanks to the wonders of medical science. So far, so boring, but this framing device is just the tip of the iceberg. As well as the doctor’s voice-over, horror star Bela Lugosi features as a god-like figure called The Scientist, sitting among voodoo totems and bubbling lab equipment, making powerful statements like “Bevare the big green dragon that sits on your doorstep!” and “Pull the stringks!” There’s a surreal dream sequence involving Glen, Barbara, and a devil (played by the wonderfully named Captain DeZita, who also intriguingly plays Glen’s father in one brief scene – whether the connection is meant to be noticed remains unknown). A whole host of off-screen voices make bizarre claims about transvestites, while the doctor continues with his scientific lecture, emphasising that Glen is “not a homosexual” and arguing that men suffer from receding hairlines due to their hats being too tight. At one point Barbara asks Glen what’s troubling him, and a herd of stampeding buffalo suddenly burst onto the screen. The story is entirely abandoned for some eight minutes towards the end, when a series of burlesque scenes involving scantily-clad females tying each other up interrupts the action. There’s no sense of time passing, no real narrative progression, no believable connection between the transvestite and the hermaphrodite. No wonder Glen or Glenda has been considered one of the worst films of all time.

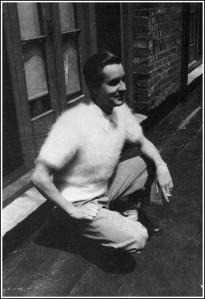

And yet. Glen or Glenda doesn’t appear in IMDB’s Bottom 100 (indeed, no Ed Wood movie does, despite his fame). In badfilm writing, there’s a strange tension when it comes to Glen or Glenda. It has to get mentioned, because to not acknowledge it would be to imply a serious omission in knowledge, but the actual reviews are frequently far more sympathetic and supportive than one might expect. Much is made of the personal, biographical nature of the film: Wood was a transvestite himself, and he plays Glen. His then-girlfriend Dolores Fuller is Barbara. In one particularly iconic scene, recreated in Tim Burton’s excellent biopic, Barbara demonstrates her acceptance of Glen’s alter-ego by symbolically removing her angora sweater and handing it to her fiancé – as any Wood fan will be aware, the filmmaker had an angora fetish that pops up in many of his movies. So much of the film seems biographical: the doctor’s claims that Glen’s mother wanted a daughter and dressed her son up as a girl; remarks about soldiers wearing lingerie beneath their fatigues – these are personal touches, little insights into the filmmaker himself. Even the fact that the film’s message is one of tolerance, emphasising the internal struggle of men who cannot reveal their true identity to the world, is because of Wood’s own struggles – the film, produced by exploitation magnate George Weiss, was originally meant to capitalise on the scandal of Christine Jorgensen’s sex-change operation, but Alan/Ann’s story is completely sidelined, given only a brief mention towards the end of the movie.

The exploitation origins of Glen or Glenda are crucial also. Classical exploitation had its own distinctive style – anyone interested in reading more should check out Eric Schaefer’s excellent book. These movies eschewed the conventions of classical narrative cinema, positioning themselves as a lecture or documentary rather than fiction, as a way of bypassing censorship. By emphasising the “educational” and cautionary aspects of the film, exploitation filmmakers could show all the shock and scandal they wanted. If Glen or Glenda seems particularly incoherent and bad in the context of classical narrative cinema, when compared to other exploitation films of the period, it’s unexpectedly generic.

So much has been written about Glen or Glenda, and so much has been repeated that it often feels as though there’s nothing new left to say. It has been “riffed” and mocked as a bad movie, praised as a deeply personal, if naïve, insight into a filmmaker struggling on the fringes of Hollywood, reclaimed as an avant-garde work of art. Personally, I struggle with the latter position – a work of art suggests something has been deliberately created. Through his own incompetence, somehow Wood has managed to create a film that is so incoherent and illogical, so cobbled together, that it encourages the audience (if they are so inclined) to actively search for justification, to find some way of explaining the weirdness on screen. Yet was Wood himself ever aware of his affect? Probably not. Was he trying to subvert conventions? Doubtful, when Glen or Glenda is so typical of the style of other classical exploitation at the time. Yet he was trying to get his message across. His plea for tolerance and understanding completely dominates the film, bringing a truly (if unintentionally) personal twist to the events on screen. For viewers who are so inclined (and many are), it’s this fact that makes the film so endearing, so sympathetic, so fascinating. Glen or Glenda originated as a generic exploitation film and became a bad movie. It’s still both those things, but such is the film – and filmmaker’s – reputation today that it transcends such seemingly reductive categorisation.

Bonus! You can watch Glen or Glenda in its entirety here!